Houston after Harvey, a critical disaster studies project

Anthropologists tell us that disasters are complex events. They result from the interactions between hazards, which may occur naturally, and human activity, or rather, the impact that hazards have on our social worlds when we are unable to adequately adapt to them. These fragile social worlds combine our existing techno-social adaptations to the environment with the nuances of place, culture and history. They invariably reflect both the limits of our own capacities as humans vis a vis the environment, and the social and economic inequalities that characterize how we use resources, organize ourselves in space, and give meaning and value to place and belonging. Disasters are events that reveal the unequal distribution of vulnerability and risk, but also the unequal capacities of human populations to withstand their impacts, and embark on a path to recovery. People are affected differently, and their abilities to recover also play out unequally.

One project undertaken by Dr. Raja Swamy, with the assistance of graduate students Thomas Tran and Julian McDaniel – and funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation – concerns the complex effects of Hurricane Harvey on the city of Houston. In 2017, the sprawling city of 6 million was devastated by an Atlantic hurricane that dumped about a trillion gallons of water within four days, overwhelming the city’s drainage systems and leaving entire neighborhoods inundated for days. While the flooding was widespread, its impacts were more pronounced in neighborhoods already facing numerous ecological and socio-economic vulnerabilities. Houston is home to one of the largest concentrations of petrochemical plants in the world, with most of these located in areas with large Black and Latinx populations. In addition, a lax regulatory regime has encouraged the proliferation of various industrial activities within neighborhoods at levels that exceed what is permissible in most other American cities. Thus one might find metal recycling, fertilizer manufacturing, car-crushing, or concrete batch processing plants interspersed in neighborhoods alongside homes, parks and schools. Secondly, several areas of the city have been targeted for gentrification, affecting historic Black neighborhoods in the city by pricing residents out, while seeking to attract higher income residents. Both these processes were important to consider as we commenced a study of the long-term processes of recovery.

What we found

One year after the disaster recovery was still a long way off for a very large number of people. One reason for this was that many poorer residents found it extremely difficult if not impossible to obtain federal aid from FEMA. This had the effect of exacerbating already difficult situations with many residents having to avail of loans or forego basic necessities in order to sustain themselves without sufficient aid. The pattern did have racial undertones as well, with Black and Latino working class communities more frequently denied aid.

The processes that presented serious challenges to residents prior to the disaster – namely exposure to dangerous levels of toxic chemicals in many neighborhoods, or gentrification in others, have continued unabated or intensified. We identify the causes for this in the manner in which the recovery process itself was construed by decision makers as an opportunity to make the goals of recovery synonymous with promoting the needs and interests of industries and property developers.

Toxicity and environmental (in)justice

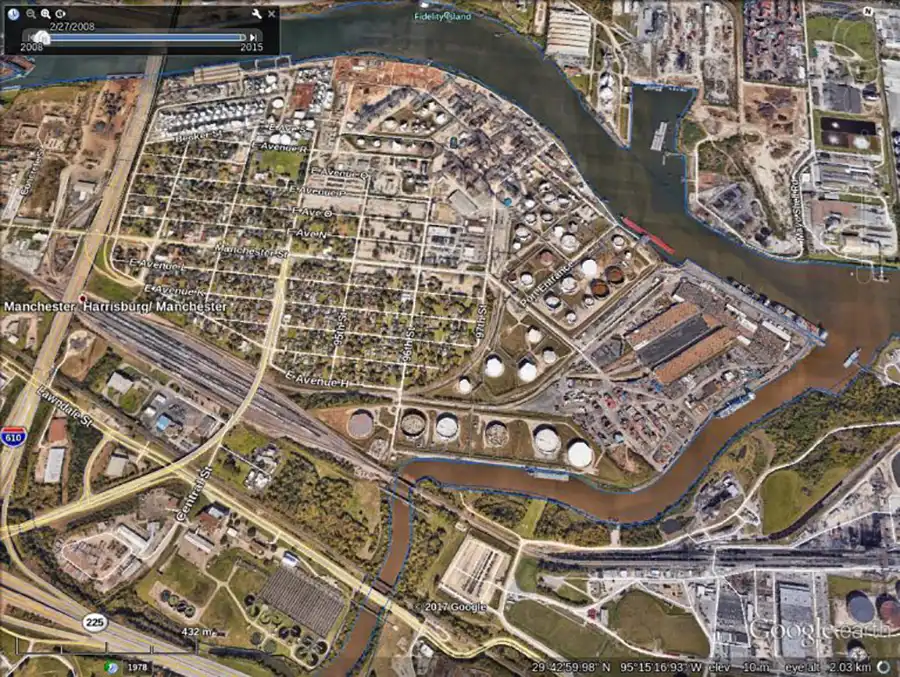

Manchester, a predominantly Latinx neighborhood on the Houston shipping channel is the site of a massive Valero refinery. While prior to the disaster the plant was associated with a host of health problems in the neighborhood, it released large quantities of Benzene during the flooding following Harvey when one of its massive storage units failed. In the year that followed however, instead of facing any consequences or scrutiny for this event, Valero sought and obtained permission from the TCEQ (Texas Commission for Environmental Quality) to release more than 500 tons of Hydrogen Cyanide per year into the air. Regulatory bodies such as the TCEQ have been frequently accused by neighborhood residents as well as environmental and social activists of acting on behalf of polluting industries more so than affected communities.

Housing and gentrification

Considered the third fastest gentrifying neighborhood in the country prior to the disaster, Houston’s Navigation Boulevard (EaDo) is home to an old Mexican American neighborhood. Post Harvey, new condominiums are being built and whiter, more affluent residents moving in, with signage extolling the “flood proof” qualities of these homes, even as Mexican American residents across the street are being pressured by developers to sell their homes. Other areas such as the historic Black neighborhoods of the 5th ward have seen a spurt of efforts by developers eager to cash in as largely Black and Latino low-income homeowners face difficulties repairing flood damaged homes. In some cases landlords have raised rents to price residents out or to force them to pay for the costs of repair, often because they have had a difficult time obtaining federal aid.

Community responses: environmental justice and civil rights activism

Throughout our research we were able to gain insights into the problems and challenges of recovery facing communities by listening to and observing the work of environmental justice and community activists working both in the process of disaster recovery as well as on the long-term issues of toxicity and gentrification. These include TEJAS, Air Alliance Houston, West Street Recovery, and the Montrose Center. These organizations enabled Houstonians to have their voices, perspectives, goals and concerns heard in various public fora, but also actively sought to promote a just and accountable recovery process. Their work extends beyond the scope of the disaster itself, reminding us that the disaster itself foregrounds and lays bare underlying social crises manifest in environmental injustice, economic and social inequality, and patterns of unaccountable power.

Further work:

Graduate student Julian McDaniel has been compiling a database of industrial accidents in Houston which is currently being transformed into a map-enriched online digital archive. Alongside this digitization project Thomas Tran is leading a project to develop a mapped dataset of impacts and recovery drawing on key insights gained through ethnographic fieldwork conducted over the course of two years in the city. In addition, Dr. Tamar Shirinian has begun a research effort to examine links between trauma and recovery related to the effects and aftermath of Hurricane Harvey as well as the longer-term crises associated with toxicity, segregation, and gentrification in the city.

Takeaways from our project:

- Conditions and problems that existed prior to a disaster are critical to an understanding of how a disaster affects different groups of people differently.

- Understanding long-term “normalized” conditions such as toxicity and gentrification helps shed light on:

- why and how communities struggle with recovery

- how policy makers prioritize industry and developer perspectives and interests over community needs.

- The challenges of recovery must include fundamental questions around environmental justice and the rights to the city.

- Local efforts addressing short and long-term needs of communities show that recovery is a complex and multifaceted goal, often in conflict with what official policies prioritize.

- Coastal urban populations living in proximity to toxic industries such as those in Houston face at least three types of hazards:

- the long-term “slow violence” of toxicity

- the directly destructive impacts of hurricanes or other hydrological events

- secondary and tertiary disaster situations as toxic hazards are released into the air, water, and soil.

- The combination of exposure to multiple hazards and the long-term effects of social inequality combine to make recovery not just a long-term process, but in some cases an impossibility.