The Conversation: ‘COVID modelling reveals new insights into ancient social distancing – podcast’

Five years since COVID emerged, not only has the pandemic affected the way we live and work, it’s also influencing the way researchers are thinking about the past.

In this episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast, archaeologist Alex Bentley explains how the pandemic has sparked new research into how disease may have affected ancient civilisations, and the clues this offers about a change in the way humans designed their villages and cities 8,000 years ago.

As an anthropologist and archaeologist at the University of Tennessee, Alex Bentley usually spend his time studying neolithic farming villages. But in the early days of the pandemic, he decided to team up with an epidemiologist on a research project to model the feedback loops between social behaviour, such as wearing a mask or not and the spread of disease. He says:

In doing that project, we learned so much about the spread of disease and its interaction with different behaviours. It was a perfect setup for looking at the same kind of question in the distant past when diseases were evolving for the first time in dense settlements.

Bentley was particularly interested in whether it could shed light on a conundrum: a curious pattern from the archaeological record that showed that early European farmers lived in large dense villages, then dispersed for centuries, then later formed cities again, which they also abandoned.

All this was happening in the neolithic period, between around 9000BC and 3000BC, a time when humans shifted from a nomadic hunterer-gatherer lifestyle to settling in small tribes in one place, cultivating the land and domesticating animals.

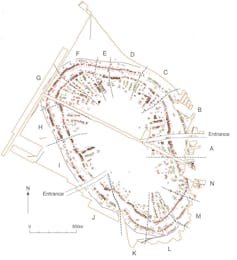

Bentley decided to apply the same model of how disease and patterns of behaviour spread during COVID, to map out how a contagious disease could have spread in an mega settlement called Nebelivka in modern-day Ukraine. This settlement was designed in an oval layout and divided into neighbourhoods, or clusters. Bentley and his colleagues suggest this layout, whether the inhabitants knew it or not, could have helped prevent the spread of disease.

Listen to the full episode of The Conversation Weekly to hear the interview with Alex Bentley.

This episode of The Conversation Weekly was written and produced by Katie Flood and hosted by Gemma Ware. Sound design was by Eloise Stevens and theme music by Neeta Sarl.

Newsclips in this episode from ABC News.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.

Gemma Ware, Host, The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.