Steven Lautzenheiser in ‘The Conversation:’ Why can’t I wiggle my toes one at a time, like my fingers?

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why can’t I wiggle my toes individually, like I can with my fingers? – Vincent, age 15, Arlington, Virginia

One of my favorite activities is going to the zoo where I live in Knoxville when it first opens and the animals are most active. On one recent weekend, I headed to the chimpanzees first.

Their breakfast was still scattered around their enclosure for them to find. Ripley, one of the male chimpanzees, quickly gathered up some fruits and vegetables, sometimes using his feet almost like hands. After he ate, he used his feet to grab the fire hoses hanging around the enclosure and even held pieces of straw and other toys in his toes.

I found myself feeling a bit envious. Why can’t people use our feet like this, quickly and easily grasping things with our toes just as easily as we do with our fingers?

I’m a biological anthropologist who studies the biomechanics of the modern human foot and ankle, using mechanical principles of movement to understand how forces affect the shape of our bodies and how humans have changed over time. Your muscles, brain and how human feet evolved all play a part in why you can’t wiggle individual toes one by one.

Comparing humans to a close relative

Humans are primates, which means we belong to the same group of animals that includes apes like Riley the chimp. In fact, chimpanzees are our closest genetic relatives, sharing almost 98.8% of our DNA.

Evolution is part of the answer to why chimpanzees have such dexterous toes while ours seem much more clumsy.

Our very ancient ancestors probably moved around the way chimpanzees do, using both their arms and legs. But over time our lineage started walking on two legs. Human feet needed to change to help us stay balanced and to support our bodies as we walk upright. It became less important for our toes to move individually than to keep us from toppling over as we moved through the world in this new way.

Human hands became more important for things such as using tools, one of the hallmark skills of human beings. Over time, our fingers became better at moving on their own. People use their hands to do lots of things, such as drawing, texting or playing a musical instrument. Even typing this article is possible only because my fingers can make small, careful and controlled movements.

People’s feet and hands evolved for different purposes.

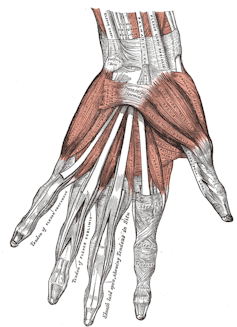

Muscles that move your fingers or toes

Evolution brought these differences about by physically adapting our muscles, bones and tendons to better support walking and balance. Hands and feet have similar anatomy; both have five fingers or toes that are moved by muscles and tendons. The human foot contains 29 muscles that all work to help you walk and stay balanced when you stand. In comparison, a hand has 34 muscles.

Most of the muscles of your foot let you point your toes down, like when you stand on tiptoes, or lift them up, like when you walk on your heels. These muscles also help feet roll slightly inward or outward, which lets you keep your balance on uneven ground. All these movements work together to help you walk and run safely.

The big toe on each foot is special because it helps push your body forward when you walk and has extra muscles just for its movement. The other four toes don’t have their own separate muscles. A few main muscles in the bottom of your foot and in your calf move all four toes at once. Because they share muscles, those toes can wiggle, but not very independently like your fingers can. The calf muscles also have long tendons that reach into the foot; they’re better at keeping you steady and helping you walk than at making tiny, precise movements.

In contrast, six main muscle groups help move each finger. The fingers share these muscles, which sit mostly in the forearm and connect to the fingers by tendons. The thumb and pinky have extra muscles that let you grip and hold objects more easily. All of these muscles are specialized to allow careful, controlled movements, such as writing.

So, yes, I have more muscles dedicated to moving my fingers, but that is not the only reason I can’t wiggle my toes one by one.

Divvying up brain power

You also need to look inside your brain to understand why toes and fingers work differently. Part of your brain called the motor cortex tells your body how to move. It’s made of cells called neurons that act like tiny messengers, sending signals to the rest of your body.

Your motor cortex devotes many more neurons to controlling your fingers than your toes, so it can send much more detailed instructions to your fingers. Because of the way your motor cortex is organized, it takes more “brain power,” meaning more signals and more activity, to move your fingers than your toes.

Even though you can’t grab things with your feet like Ripley the chimp can, you can understand why.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Steven Lautzenheiser, Assistant Professor of Biological Anthropology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.